Welcome back to this second essay in my new series about fermentation – and how it might influence your life…

We ended the last essay with a rather straightforward question: What, exactly, is fermentation?

But while the question might be straightforward, alas, the answer isn’t as simple as one might assume it should be. In fact, there are several answers, and two particular hurdles we’ll have to overcome in figuring them out.

The first of these hurdles is a matter of boundaries:

Before we can define our understanding of the term “fermentation”, we need to agree on which processes we’re going to include under the broad umbrella of “fermentation” in the first place – and which ones not.

This might seem like circular reasoning at first: If we agree on what fermentation is, we know what fermentation is, or something to this effect. 😉

But the matter is a bit more subtle, and also more profound: In order to figure out what the term “fermentation” means, we need to first agree on what, exactly, is even covered by this term.

So let’s start out with something we already encountered in my basement in the last essay, something we know and agreed upon: Sauerkraut should most definitely be covered by our understanding of the term fermentation.

Or, in other words: When we start out with a heap of sliced cabbage and end up with sauerkraut, what happens in between is this mysterious thing called “fermentation” which turns the former into the latter.

So far, so good. 🙂

But what about other things? Are they a product of fermentation, or aren’t they? And this is where things get dicey…

For sure, there are a lot of things which are clearly products of what we call fermentation, just like the sauerkraut. There are also even more other things which clearly aren’t.

(For example, if I boil dried, store-bought pasta in order to serve spaghetti bolognese, there is no fermentation involved in this boiling process.)

But at the edge, where the ferments and the non-ferments meet, there is a grey zone. And as so often in life, this grey zone, the area where things are somehow part of the group, but then also somehow not, is where it gets interesting. Again as so often in life, though, it’s also the hardest to grasp and to define.

Thus what we will do in this and especially in the next essay is take the smart approach and start out with some obvious cases, and then feel our way forward from there. Before we do so, though, we need to quickly talk about the second of the hurdles which we’ll encounter in defining what “fermentation” is.

You see, our understanding of the term fermentation depends greatly on our outlook. Depending on the vantage point we choose, we’ll get very different insights into fermentation, and correspondingly will understand it in very different terms.

We could, for example, talk about fermentation from a practical perspective – and in fact we’ll do so very soon.

We could also consider fermentation from a spiritual or religious viewpoint. Or from a sociological or ethnological one. From process-oriented thinking or from microbiology. From health concerns, or from aspects of food safety. Or, of course, from the vantage point of somebody who simply relishes delicious foods.

And during the course of this essay series, we’ll take on all of these viewpoints, in one way or another.

For today, though, I want to focus on another aspect of fermentation, another level on which we can aproach it, and that’s from a scientific point of view.

Now, we won’t go very far into this angle, and there certainly won’t be any formulas or other complicated stuff – mainly because I’m not a chemist or biologist and I don’t intend to play one on TV.

Of course, it also doesn’t help the matter that I find this scientific approach to fermentation rather dull and unhelpful for the purpose of this series, and would much rather get on to the practical stuff and any insights we can gain from it. 😉

Still, I feel it’s helpful to understand at least some basics about fermentation from a scientific perspective. And some of the distinctions and insights we can gain from it will be helpful later on in your practical work, e.g. to distinguish between different kinds of fermentations and their differing needs.

So let’s grit our teeth and get this over with, shall we? 😀 (Just kidding – I promise it won’t hurt at all!)

From a scientific perspective, fermentation is a type of anaerobic metabolic process. In everyday terms, this means three things:

First, there is a process or some kind of change going on during fermentation – although seriously, this shouldn’t come as a big surprise, given the transformation from sliced cabbage to sauerkraut!

Secondly, it happens under anaerobic conditions, i.e. without oxygen.

And thirdly, somebody is digesting something during this process.

It might feel a bit weird to think about fermentation in these terms, but that’s really what it is: Tiny little critters munching away on the sugars and starches in your ferment. And in the process, they both change the ferment and produce and output certain other things (which then also turn your ferment into something different).

We will look at these critters and their contribution in much more detail later. For now, suffice it to say that we’re talking about bacteria and yeasts – of the beneficial, healthy, and edible kind, not of the yucky or unhealthy kind!

Science also helpfully distinguishes between two kinds of fermentation (or three, but we’ll get to the third one below): Lactic acid fermentation and alcoholic (or ethanol) fermentation.

Sauerkraut, as you might have guessed, is the result of a lactic acid fermentation. (The only alcohol in good kraut is some white wine added during the cooking process!) Yogurt is another example of a lactic acid fermentation – the slightly sour taste it features compared to milk is just this, lactic acid. Yet others are pickles or kimchi.

Certain other ferments are clearly of the alcoholic kind: wine, for example, or beer.

There are also certain kinds of ferments for which my (admittedly superficial) internet research didn’t deliver a clear result as to their type – and funnily enough, the product of this essay’s Hands-On Fermentation Homework is one of them: Some sources proclaim it’s lactic acid fermentation, others insist it’s alcoholic fermentation.

(To be honest, I don’t really care. The outcome, eventually, tastes amazingly good, and smells even better – and in some cases, taste and smell are a lot more important than getting the scientific labels right! 😉 )

But be that as it may, scientific research tells us there are yeasts and bacteria which, during fermentation, digest sugars and starches – and output acids. And to top it off, they blow out some gases, too!

Thus ferments are well and truly alive, even if we can’t see the wee critters which do all the delicious and beneficial work for us.

So in a way, home-fermenting is like having your very own herd of productive livestock, right there in a glass jar on your kitchen counter!

(On the other hand, a case could be made that it’s not you who is keeping the fermentation critters, but it’s them keeping you. But that’s a topic for another day… 😉 )

At this point, we could go deeper into biology and discuss the kinds of critters which ferment for us, their metabolisms, life cycles, living conditions and reproduction.

We could also go deeper into chemistry and break down the actual changes in all the affected substances in detail.

We could also go into biotechnology and explore the various ways in which the process of fermentation is being used for research and for producing things.

All of these are viable areas of interest, but as I said above, I don’t find them very helpful in the context of this essay series. Thus if any of this rocks your boat, you’re on your own from here on and will need to do any further research for yourself.

What I’d like to do instead, is go on a brief foray into what is yet another kind of fermentation… or is it?

‘Cause this third kind of fermentation leads us straight into the grey zone, the area where things can both be a kind of fermentation, and not be one – at the same time…

And by going into these borderline cases, we’ll learn some important things about fermentation, too.

You see, most definitions of fermentation, like the one I explained a bit further up, involve some mentioning of the term “anaerob”, meaning without oxygen. According to them, fermentation is an anaerob process – no oxygen involved.

But then there is allegedly also a third kind of fermentation, namely acetic acid fermentation. Or, in other words, the kind which produces vinegar.

(Have you ever had a bottle of wine go bad on you and tip over into vinegar? That was the result of this process.)

The difference between a fermentation stopping at wine, and a fermentation tipping over into vinegar is simply… oxygen. While wine ferments in closed caskets, without oxygen, if you leave it standing in the open and there are live fermenting critters around, they will ferment it into vinegar by using the available oxygen.

But hang on, didn’t we say above that fermentation is an anaerobic process, i.e. it happens in the absence of air? Well, yes and no. “True” fermentation is, but of course there is also this huge grey zone… 😉

Thus even on this level of simple scientific description, where we tend to assume things are clearcut and straightforward, there are different ways to describe fermentation. And which way is the most productive depends on one’s specific needs and purposes, i.e. what one is trying to produce or to research.

We’ll go into the matter of wine vs. vinegar, oxygen or not, in more detail in a later essay.

For today, I’m happy to declare that this is it, as far as scientific explanations are concerned: This is about the maximum level of scientific complexity and depth into which we’re going to plunge in this series – not as bad as some of you might have feared, I hope! 😀

(Although I certainly won’t mind people discussing scientific details of fermentation in the comments. Well, as long as you know what you’re talking about. 😛 )

So what have we gained from today’s foray into the scientific shallows of fermentation?

Well, we now have a general idea of what fermentation is, and how it happens – although for some of you, all of this might be ancient history.

But more importantly, we’ve encountered two important hurdles concepts which we’re going to draw upon later in the series:

The idea that there are different levels on which to perceive and describe fermentation. And the idea that fermentation is a broad field and doesn’t just consist of clear-cut cases – there are also things which are somehow fermentation, but then somehow not quite.

Do we need to make clear-cut scientific distinctions? E.g. about the type of fermenting critters which do the work for us? Or about the kind of fermentation we’re dealing with? Or about aerob or anaerob, and what counts as fermentation?

And more generally, do we need to limit ourselves to just one specific level on which we explore fermentation?

Of course not. We can hop around on different levels, and take on different vantage points as we please. We can also simply ferment to our heart’s content, enjoy the fruits of our experiments – and learn a lot about ourselves and the world in the process…

During the course of this series, we’ll do all this and more!

For today, we have settled on a rough idea of what fermentation is – on paper, that is. And today’s homework’s will help you to transfer this book knowledge into something more tangible, and more useful…

Inner Fermentation Homework

In this essay, we’ve encountered two hurdles on our path to a clearer understanding of the term “fermentation”.

(Or rather, I have identified two hurdles. But then you didn’t object, so I’m afraid you’re in for it now… 😛 )

The first hurdle was to even identify which examples are fermentation, and which aren’t, with a particular eye to the grey area in between the two. It’s in this grey area where some interesting things happen. It’s also this grey area which helps us to clarify and sharpen our understanding of the term even further by figuring out how we define it, and what we include in it and what not.

Incidentally, it’s also this grey, somewhat undefined area which is a huge hurdle in many kinds of conflict between people… Just because two people are both talking about dogs, or about peace, or about ethical or moral values, or about all kinds of emotional upheaval, or what not else, doesn’t mean they are actually talking about the same things.

A great many conflicts could be resolved, and a great many pointless arguments avoided, if everybody involved took the time to take a step back, and first figure out what exactly they themselves are talking about – and what the other person is talking about. In a lot of cases, it won’t be the same.

The second hurdle consisted of the fact that there are different viewpoints onto an issue, and different levels on which to understand it.

You could approach an issue e.g. from a schientific angle, on the emotional level, on the plane of relationships, and so on. (Which levels or viewpoints will be possible and helpful depends on the issue in question, but there is always more than one, and usually at least a few.)

Your Inner Fermentation Homework for this essay, then, is to consider these two hurdles, and to apply them to your own life. If you encounter any challenge, any kind of conflict, or any other problem or issue, take a few minutes to approach them with an eye towards these two hurdles:

What, to you, is definitely included in the issue? What is definitely not included?

And the part where it gets interesting:

What is in the grey area? E.g. by being partially included. Or kind of related. Or to some extent relevant. Or by being a borderline case.

If there are other parties involved, bonus points if you also try to figure out their zones of “definite yes”, “definite no”, and their grey area!

And the same for the second hurdle we’ve discussed in this essay:

On which level are you approaching the issue? From which viewpoint?

Are there other levels which would also be possible? Why have you chosen the one you have chosen, and not the others?

Is/Are there any which might be more productive? Or also helpful?

Even if not, spend a bit of time on perceiving the issue on these other levels, and get a feeling for it from these angles.

And again, if there are any other people involved, try to figure out on which levels they are operating.

Are they the same as yours, or different? And why?

Would there be any way to establish a shared viewpoint? For you to approach them on the level they have chosen? Any way to at least establish a shared language, symbolism or understanding of the issue in question?

You don’t need to do anything with your insights (although you are certainly welcome to apply them in any way you see fit!). Simply think about these things, try to figure them out, reflect on them… and perceive how this alone changes certain aspects of the issue… 😉

If possible, work with these ideas all throughout the two weeks until the next essay goes up. If you can’t incorporate them daily, that’s fine – but keep them in the back of your mind as well as you can, if at all possible take a bit of time each day for actively reflecting on them… and see where it will lead you! 😉

Hands-On Fermentation Homework

Your practical fermentation homework this week is something which isn’t edible in itself (well, it is edible, but it’s not an enjoyable treat all on its own) – but it’s the basis for some very tasty things we’re going to ferment over the course of the next few essays. But today’s Hands-On Homework is not just useful, it’s also an easy start into fermentation for those who don’t have much experience with it!

What you’re going to ferment this week is a sourdough starter.

(If you should already happen to have one bubbling away in your kitchen, of course there is no need to get a second one going. In this case, please feel free to skip this homework!)

Now, I have to admit I’m not an expert in sourdough starter fermentation. In fact, I’ve only done it twice in my life: The first time failed, and the second time turned out so well that we’re still using the same starter today, several years later…

This means I had to look up the process again for this essay, since it’s been a while that I did it. 😉

It also means I know from firsthand experience that yes, your first try at fermenting a sourdough starter might fail. But I also happen to know from firsthand experience that this isn’t a biggie, and you can simply start over and then be successful.

I also know it’s dirt simple, easy-peasy – and it doesn’t require much equipment, and only two simple ingredients.

(Besides, if even I got it done, albeit needing two attempts, you’ll certainly be able to create your own sourdough starter as well!)

If you should have no clue what a “sourdough starter” even is, btw, then don’t despair. In this homework, you will learn how to get one going, and how to keep it alive for the next two weeks. In the next essay, we’ll begin to actually create awesome goodies with it, and you’ll understand immediately why it’s called a “starter”! 😉

Stuff you need

What you’ll need for your own personal sourdough starter is

- flour,

- water,

- and a glass jar of suitable size

Flour

For the flour, your best choice is rye flour, and if possible whole-grain rye flour.

The reason for this is simply that the sourdough cultures love rye the most, and whole-grain flour gives them more food to digest. Both things make it easier to establish a sourdough starter culture from scratch.

On the other hand, if all you can get is non-whole-grain rye, or only wheat or spelt flour, then don’t give in – just go for it.

As is often the case in fermentation (and we’ll talk about this in a later essay in depth), the choice of flour isn’t a black-and-white matter. Instead, certain things simply increase your chances of getting good results. If you can’t or don’t do them, your odds might be a bit worse, but are still more than good enough to get great results in most cases!

So get whole-grain rye flour if possible, if not other kinds of rye flour, or if not then wheat or spelt flour will be fine.

Water

The second ingredient you’ll need is water. For this, plain tap water will do – but only if it’s not too heavily treated.

If your tap water is very strongly chlorinated, you can leave it out for a few hours or a day, to let the chlorine evaporate: Simply put water into a broad pot or bowl, and let it stand uncovered.

Your other option is to boil the water, which will also make the chlorine evaporate. If you do this, though, you’ll need to let the water cool down to body temperature or less before using it for your starter, otherwise it’ll be too hot for the fermentation process.

(Apparently some kinds of chlorine additives don’t evaporate well by just leaving the water out uncovered. If yours should still taste or smell chlorinated after a day or two, try boiling – or see below for alternatives.)

If your tap water should contain other additives like fluoride, you’ll be best off getting water from elsewhere. These additives might disturb the fermentation – but even if they shouldn’t, the question is whether it’s smart to amass larger amounts of these additives in your ferments and thus in yourself…

An alternative to tap water is bottled water or, if you have a suitable spring with potable water nearby, of course spring water. For bottled water, take one which isn’t particularly rich in certain minerals (i.e. not a “mineral water” advertized as “high in XX”), and of course a non-sparkling one. Or if you happen to have a water filter which reliably filters additives like fluoride, then of course you’re also covered.

Generally, though, please don’t sweat it too much about the water. I’ve been fermenting everything with our local tap water, and have never had any problems with it. That’s to say, you don’t need the water from the fairy spring deep in the untouched woods, at the foot of the old, mistletoe-covered oak, harvested only when the waxing moon is in a cetain sign. 😉

Plain, simple, and uncomplicated works amazingly well for fermentation!

Instructions

Creating a sourdough starter from scratch is a process which takes several days, and which will, incidentally, also make you acquainted with some key elements of working with ferments. 😉

Also, and with a very sincere apology to my US readers, throughout the series I’m going to use weight measurements, and not cups or spoons (i.e. volumes). If you absolutely insist on sticking with your cups and spoons, or if you simply have no scales at hand, you’ll need to find an online conversion tool or conversion list for the specific ingredients we use…

Day 1:

Mix 50 grams of your flour and 50 grams of water. If the resulting “dough” should be very dry and hard, add just a tiny bit more water. You should end up with a soft paste which isn’t actually runny, but is definitely not crumbly or dry either! This is the start of your starter. 😉

Put it into a glass jar, and cover losely with a lid.

The jar should be large enough to hold roughly ten times the amount you put into it today. If in doubt, a bit bigger is better (although you can always scrape your starter into a bigger jar later if necessary).

“Cover losely” means you want to put a lid on, but allow gases to get out of the jar. During fermentation, certain gases are produced.

If your jar is shut tightly, an overpressure will build, and worst case you’ll end up with an exploding jar, glass shards all over the place, and sticky blobs of sourdough starter on your walls. So make sure the lid is only put on losely, and gases can escape without building up pressure!

Keep the glass in a warm place, but not overly hot, and not in direct sunlight. 25-30 degrees Celsius would be ideal, but I’ve done mine successfully in our kitchen, which definitely didn’t have 30 degrees Celsius at that time! 😀

Generally speaking, the cooler it is, the longer a fermentation process takes. But if things are too cool, the fermentation won’t get going at all, and instead other, less desirable processes will take over (and lead to rather unpleasant results).

I.e. a comfily warm environment is important for your starter at this stage. Once it’s safely established, it will even tolerate the fridge – but that’s still a few days out…

On the other hand, a reasonably warm kitchen will be perfectly fine. There is no need to worry about hitting exactly 25 degrees Celsius! As a rule of thumb, if you’d be fine in, say, a shirt or a light sweater, your starter proably also will be.

If your place should be too cool at this time of the year, get creative:

Put the jar close to a heater or stove (but not right on it – if it gets too hot, you’ll kill the fermentation critters!), for example. Wrap it into a towel together with a handwarm hot water bottle, or put both the jar and a hot water bottle into the closed oven. Or if your oven should be of the old-fashioned kind, letting the oven light on with closed doors would work, too, as would a yogurt maker.

However you do it, keep your budding sourdough starter comfortably warm without overheating it, and it will be a happy camper. 🙂

Day 2:

Depending on the surroundings, you might already see the first movement in your starter: some shy bubbles, maybe, or a slight expansion. These are good signs – but if you can’t see anything yet, don’t despair, just keep it comfortable and give it more time!

Either way, you’ll need to feed it: For this, do the same as on day 1, i.e. mix another 50g batch of flour with about 50g of water, to about the same consistency. Stir this paste/dough into your existing starter. Again, cover the jar losely with the lid and let it rest.

Day 3 to 5:

Continue doing the same: Prepare a new batch of the flour-water mixture, and stir it into your starter.

By the third day, you’ll most likely see some effects: bubbles, a rising starter (i.e. an increase in volume), and/or a change in smell.

If there are no signs of any change at all, this could have several reasons:

- Your place might be too cool. In this case, if at all possible, get your starter to a warmer place now, before it fails.

- You’ve overheated your starter, or are still overheating it. This will kill the bacteria and yeasts which are at the heart of fermentation. Put it into a cooler place right away, and hope for the best – your starter might still recover through any leftover critters, or through others which are present in its surroundings.

- Your starter simply is a non-starter. In some rare cases, fermentation just doesn’t get going, for whatever reasons. As long as it doesn’t show any signs of mold, keep it and give it more time, it might just be of the slower sort and catch on a bit later.

The smell of your sourdough starter will change over time.

At first, it’s going to smell like, well, flour mixed with water. 😉 In the end, provided things ferment as they should, it’s going to have a pleasant (although potentially rather strong) and distinct sour smell.

On the road from here to there, its smell can be all over the place, while the fermentation cultures are still hashing out a working equilibrium.

So don’t be put off if the smell of your starter changes quite a bit, and might be weird or strange at times. If it should really and seriously tip over into something inedible, trust me, you will know!

The one reason to ditch your starter attempt and to start over again from scratch would be mold.

If patches of mold should develop on the surface, you might still be able to salvage the fermentation (scrape of the mold, improve the environment if necessary, e.g. warmer or cooler, and then hope for the “good guys” to take over and swing things back into the orderly lane of fermentation) – but honestly, it might or might not work at this stage.

Simply tossing your first try and starting over will be a lot more promising and way easier.

After day 5:

Once you’ve got a happily bubbling, expanding (and sometimes contracting) mass in your jar, maybe around day 5, maybe some days later, put the jar with the starter into your fridge. Don’t do this too early – if in doubt, give it another day or two with regular feedings, as explained above.

Once it’s in the fridge, the metabolism of the fermentation is slowed down, and you don’t need to feed it quite as often amymore.

Still, ferments are living things, and it will need food to survive – and we very much want it to survive, as I’ve got some grand (and very yummy) plans with sourdough for the next few weeks’ homework! 🙂

Usually, when stored in a fridge, feeding a sourdough starter once a week is perfectly fine (and a well established sourdough starter will also survive for longer without being fed). But since this is still a baby, so to speak, and the cultures will still need to finetune their delicate balance and get well established, I’d say give it new “food” twice a week, i.e. every three or four days, until the next essay’s homework.

For simplicity’s sake, you can follow the recipe above (50g + 50g), or simply go by your gut feeling (dump some flour into the glass and add some water and stir, until the consistency is about right).

Conclusions and Outlook

As I admitted above, I’m not the expert in creating sourdough starter – but I remember very well that it’s not that hard… 😉 So I hope you’ll join me in the fun-to-come, and will have gotten your own sourdough starter going by the time we dive into the next essay… and boy, will it be a delicious and mouth-watering one!

Next time, we’re going to approach the same things yet again from another angle, by exploring the question “So what is fermentation?” on a more practical level.

The next essay will go up on on Sunday, March 1st. And as usual, I’m looking forward to your thoughts, questions and comments below! 🙂

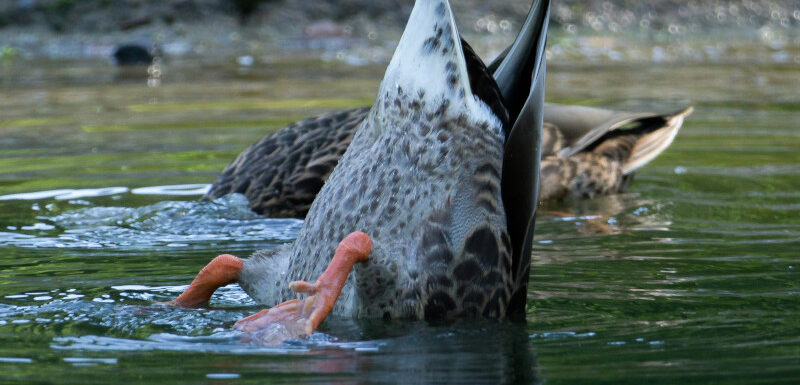

Image: Robert Schwarz on Unsplash

Leave a Reply